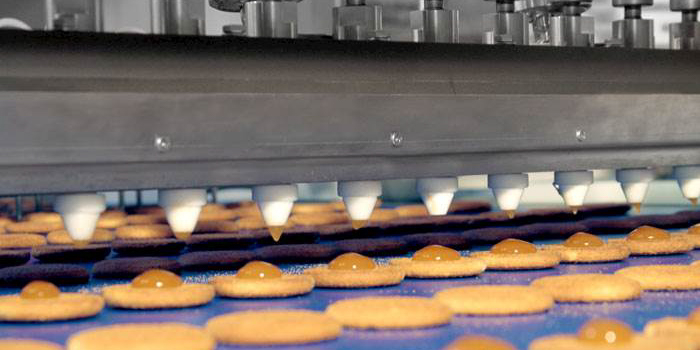

Sandwich Biscuits

Addressing baby biscuit formulation: balancing nutrition, texture, safety, and digestibility for optimal development

Explore the effects and challenges of soluble and insoluble fibers in product development. Discover new insights and application examples for bakery i...

Hemicellulases like xylanases optimize wheat flour, enhancing water binding. Xylanases and proteases synergize for superior wafer production, reducing...